Read the interview by Monika Rychlíková for Salon, a literary supplement of the daily Právo.

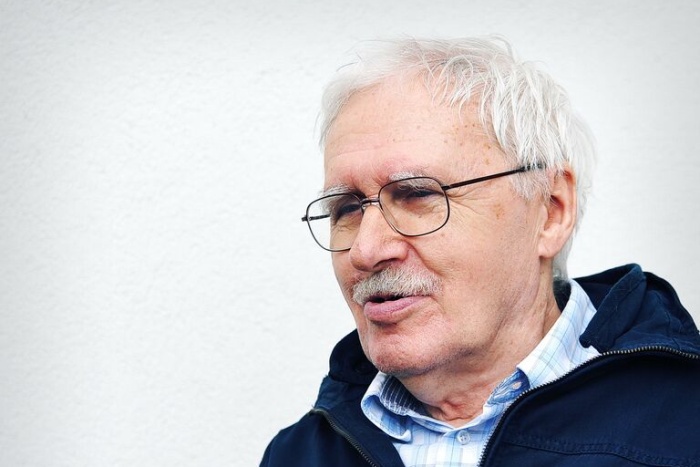

“My encounter with the dissident movement was the most important part of my life, because it’s only in such exceptional circumstances that you ever get to see the point of literature,” says Jiří Kratochvil (1940), who has been nominated for the Magnesia Litera prize for his magical realist novel Liška v dámu (Fox into Lady, Druhé město 2019), the tale of a beautiful foxy lady raised in Moscow and sent on a secret mission, who falls in love with a Brno worker groomed by the secret police during the Cold War.

Do you have some special affinity with foxes?

Well, I do actually. My novel Fox into Lady is dedicated to all the foxes in my life. I’ll just mention a couple of examples. My father used to look after injured animals and then return them to the wild, so at home we didn’t just have an eagle owl and roe deer, but also a fox. My most precious photo from my childhood is actually with my friend the fox. Fifty-five years later I met a fox on a forest path. As it was chasing a hare it came hurtling past me so close that it not only touched my leg but also raised its head and quick as a flash greeted me. At least that’s the way it looked to me. Ever since then I have called that forest path the “fox track”, and I walk it for ideas on stories and novels. When I first set out on the fox track I don’t know anything at all yet and when I come back I have an entire story or chapter of a novel at the ready. All I need to do is sit down and write.

Did Fox into Lady, the novel nominated for the Magnesia Litera prose prize, come about that way? The awards ceremony is actually taking place today.

Well as I was in the middle of one story late one evening the idea for this novel popped into my head. I discarded the story I was working on, and the next day I set off on the fox track. When I got back I already had the entire plot, though of course this was followed by the most awkward part, as for months and months I plugged away and sweated and toiled over transforming the idea into novel form. I shut myself up at home and lived like a hermit until I’d finished Fox into Lady. That is with one exception: I went off to the library for the Czech translation of David Garnett’s novel Dáma v lišku (Lady into Fox), which I was steered towards by Vercors’ novel Sylva.

Garnett tells of a lady transforming into a fox and Vercors of a fox transforming into a lady. I combined both transformations. My fox turns into a lady and then slowly turns back into a fox, the whole story being set during the Cold War, which is far removed from the context of Garnett’s and Vercors’ novels. I also settled accounts with the secret police, who descended on my life after my father emigrated when I was a child. In my novel the secret police brutally butcher one another. Moreover this is a novel about a great, indeed the greatest, love during dark times, which also sets it apart from Garnett and Vercors, but all the same together with their novels it does form a kind of trilogy.

This summer the Czech literary community has been divided by Jan Novák’s book: Kundera: Czech Life and Times. How do you see it?

If it were a new literary analysis of Kundera’s novels I’d go into town for it straight away, but a biography doesn’t interest me. Gustave Flaubert believes the author has to disappear behind his work, that is, his work is all that should be left. That’s the only thing of any actual value and the author’s life should sink into insignificance, which has not yet happened in the case of Milan Kundera, so his life is ripped apart by those wolves in his novel Pomalost (Slowness), referred to by Věra Kunderová.

I read the interview with Jan Novák in the weekly Echo, and when he says there “I write about Kundera’s sex life in quite a similar way,” then excuse me but it really is gutter press stuff, but then as a marketing move it did prove worthwhile and the book is selling more than just well.

Of course Jan Novák did not neglect Kundera’s alleged denunciation of a foreign agent. I have my own particular attitude towards this for personal reasons, as I’ve been through a similar witch-hunt during the darkest days of the 1980s, when I was unable to defend myself, as a report filtered through to the dissidents at that time that I was a secret police collaborator. This died a death after 1990, I have a vetting certificate and the person who put it about has apologized, but I can’t put that witch-hunt experience behind me, It still haunts me, so I’m especially sensitive to the subject.

I mention this here in connection with Novák’s book for one other reason, as the man behind that attack on me was a writer in exile, whose literary output was not worth a hoot, whereas at the time Jiří Gruša nominated me for the Seifert Prize and offered my novel to Škvorecký in Toronto for publication, which that writer in exile still managed to prevent. So literary envy! For anybody who’s interested in more details, I write about it in my book Avion. Milan Uhde also refers to this in his Rozpomínkách (Reminiscences).

I just want to say that literary envy is one of a writer’s worst sins – and the envious should roast on a spit in literary hell, except there’s no such thing as literary hell, so they’ll just have to stay unpunished.

When did you first realize that you might be a writer?

In the sixth form my Czech teacher foretold my future as a writer, as she stood up for me when I got into trouble because I’d been distributing my home-made westerns in class, so I repaid her by writing a story about the assassination of President Lincoln. She liked the story and read it out in the classes next door as an example of literary talent.

Although the story was never published anywhere and I’ve long forgotten its title, I shall never forget the fee I got for it, as my poetically-named classmate Jan Březina wrote another story for our teacher straight afterwards, but it wasn’t as successful as he imagined it would be. So the next day he challenged me to a proper Indian duel at one of the oak trees on Špilberk. This was just a pretext for him to beat me like a dog, frail and sickly as I was. And it was only when I read Isaac Babel’s story Můj první honorář (My First Fee) that I realized that trouncing was my first ever fee. I look back on that with nostalgia, because it was that beating, my first ever fee, that actually made me a writer. Oh, that eternal literary envy, eh? Mr Novák?

What kind of a writer are you? What literary drawer would you put yourself in?

Preferably none of them. But if I have to then magic realism. My greatest literary loves include Jorge Luis Borges, Julio Cortázar, Gabriel García Márquez and Mario Vargas Llosa, whose influence on me is undeniable. But then what good is that to me if those literary critics, those wolves from Kundera’s Slowness, have double-locked up the postmodernists in their drawer? Which I am also responsible for, because I once just happened on a whim to call one of my books of stories Má lásko, Postmoderno (O Postmodern, My Love). Serves me right. You pay for being stupid.

I’ve heard that for quite a long time you used to burn everything you wrote. Why?

At the end of the 1960s I used to publish in literary journals, particularly in Host do domu, and my first book was due to be published at Blok, but then the order came from above to exclude it from the publishing plan. Then came the 1970s, when I was running around doing various labouring jobs, but I never managed to get away from the storytelling. I was a prohibited writer without any links with the literary dissidents at that time, so I was living in a kind of literary autism, but writing away like the clappers, plugging away on story texts, recasting and polishing them. And when I’d got them into a form that would not budge any further then I would ritually burn them. Nowadays I refer to it as “three barnfuls of incinerated stories” and not a single line of them has survived.

And what was the point? Hectic story-writing just for my “readers from hell” helped me to survive those dark days. I always had one foot in the world of fiction. Never again did I have to slog away, drudge, sweat or toil over a story or novel as I did at that time in the 1970s, even though those texts were only destined for the flames.

Evidently you felt happiest on the dissident literary scene.

Now that was in the 1980s. My essay Literatura teď (Literature Now), which Jan Trefulka took with him to the Obsah samizdat editorial office in Prague decided my acceptance among the literary dissidents. The essay was accepted by Listy in exile and it was read out on Svobodná Evropa, thus I found myself in the company of Ludvík Vaculík, Lenka Procházková, Václav Havel, Milan Uhde, Eda Kriseová, Petr Kabeš, Karel Pecka and Zdeněk Kotrlý. Every three months I went along with Trefulka to what were known as quarterlies, where an issue of Obsah was put together. I contributed short stories, an extract from my novel and other essays. The Obsah editors met in the flats of Prague writers and every year in September at Hrádeček.

So there I was, a strict introvert, suddenly having a lively social life at the end of the seventies and during the eighties. My encounter with the dissident movement was the most important part of my life, because it’s only in such exceptional circumstances that you ever get to see the point of literature.

And what are you writing now following your eightieth birthday?

I’m not getting into any more novels, as I don’t have the courage, and I’m only taking away ideas for short stories from the fox tracks. I’m currently writing one that means a lot to me. About ten years ago I wrote a story with the Russian title of Ya loshad, about the liberation of Brno, and in particular the Tugendhat villa. Then it came out in an American anthology of the best European short stories. And now I’m coming back to the subject of the complicated relations between ourselves and Russia and what they’re like these days. The result is meant to be a kind of counterpart to Ya loshad.

In your Brněnské povídky (Brno Stories) from 2007 you write: “I only know one thing with any certainty: we live in a world in which we are often just unconscious intermediaries, go-betweens, mere messengers bearing messages that we cannot read or understand, mere links in a chain that we know nothing at all about.” Would you add anything to that today?

It’s still true. I, too, am just a messenger bearing mysterious messages and that’s all.

Monika Rychlíková, Salon, Právo (printed version published 26th August, 2020, online version published 31st August, 2020), translated by Melvyn Clarke

14. 10. 2020